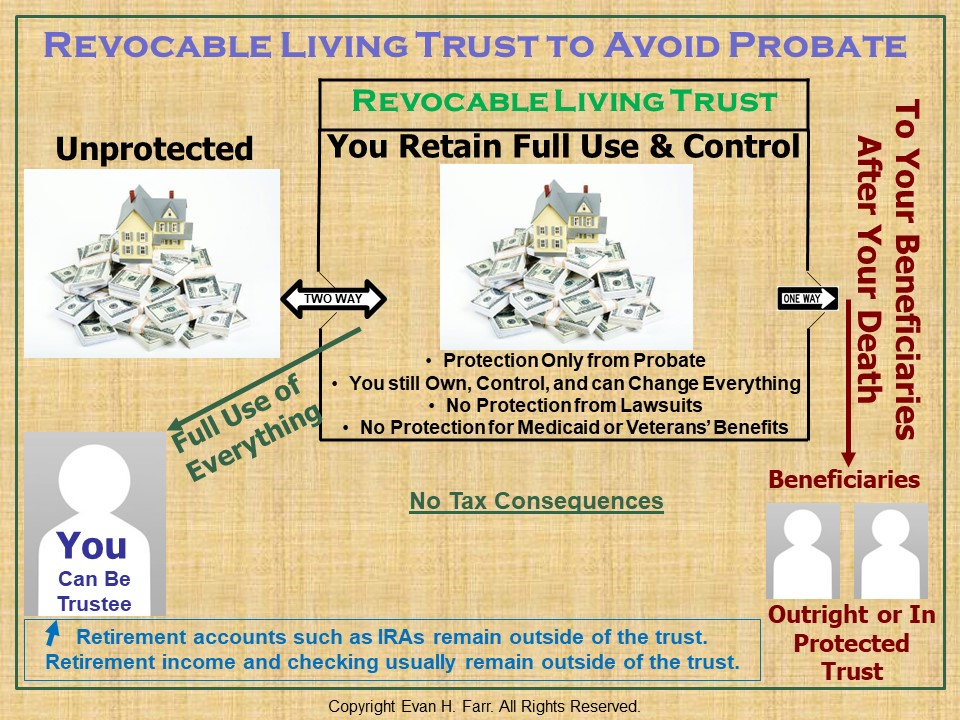

A Revocable Living Trust (RLT) generally provides for the creator of the trust (and, if applicable, the creator’s spouse) to have full use of the trust income and principal for life. On the death of the creator, the assets may continue to be held in trust (or may be distributed) for the benefit of the named beneficiaries, such as the grantor’s children. The major benefits of the RLT are avoiding probate and protection from incapacity.

Avoiding Probate

At your death, the trust assets may be quickly distributed according to the terms of the trust, without the delay, fees, and public exposure of probate. An RLT is especially recommended for anyone who owns or may in the future acquire real estate in more than one State, because without an RLT your estate will have to go through probate in both States.

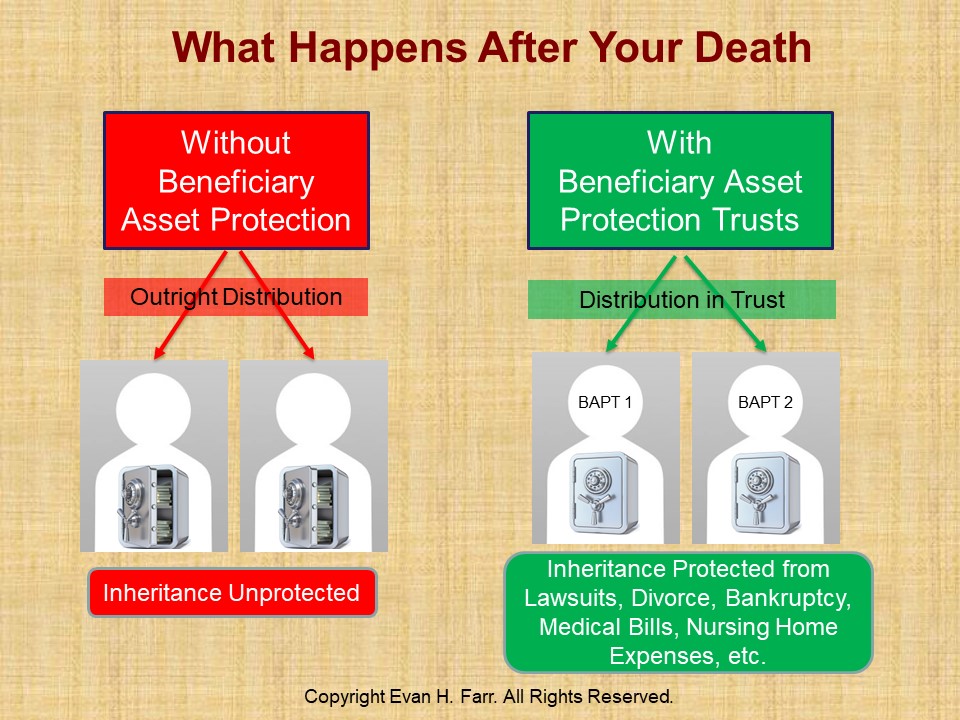

With an RLT, you can provide how the real estate and other trust property is to be distributed at your death. As with a Will, you can provide for any number of special situations. You may, for example, provide that your trustee hold and manage property to be distributed to your children when they reach the age of majority, or until a later age if you believe they need longer-term protection.

You may also provide that your trustee hold the property and distribute any income to your spouse during his or her life with the property passing to your children or other beneficiaries at your spouse’s death. Because your assets pass according to the trust instrument, they do not pass through your estate and, therefore, are not subject to the complications of probate.

Diagrams of How a Revocable Living Trust Works During Life and Upon Death

Protection from Incapacity

The RLT can provide uninterrupted management of your assets by your trustee if you become incapacitated. If illness or injury ever makes you incapable of managing your financial affairs, the trust can spare you and your family the potential publicity and expense of a court-appointed guardianship.

Without the trust (or other contingency planning device such as a durable power of attorney), there is no one with authority to manage your property. A court must judge you to be incompetent and appoint a committee or guardian to manage your affairs. That guardian could be a stranger to your family or be a family member who would normally be unacceptable to you.

Practical Considerations

There are many other practical considerations in using an RLT. An RLT does not eliminate the need for a Will. A Will is necessary to pass on those assets you have not transferred to the trust. In order to have all your assets pass through the trust, you must have a Will with a pour-over provision.

This directs any assets not already in the trust to be transferred into the trust at your death, where they will be managed and distributed as your RLT directs. Without a pour-over provision in a Will, these additional assets will pass according to your last unrevoked Will or the State law if there is no Will. An RLT can involve significant planning.

Together with your lawyer, you must develop a plan for the ultimate disposition of your property. Your lawyer will then use that plan to draw up the RLT instrument, which provides how you, as trustee, will manage your assets and how and when you will make distributions. With your lawyer’s help, you must arrange for your assets (such as real estate, bank accounts, and securities) to be transferred to the trust. No separate tax returns are required for the RLT.

The tax laws consider you as still owning the property since you still control the property as trustee. All income from the trust will be considered earned by you for income tax purposes. At your death, the property in your RLT is included in your estate for estate tax purposes.

If you do not want to transfer your assets to an RLT now but still want the protection and advantages the RLT provides, then you can establish your RLT coupled with a durable power of attorney. The trust agreement will be executed, but the RLT will be funded with only a nominal sum. The trust will exist on a “standby” basis, awaiting the receipt of your assets if you become incapacitated. Your power of attorney gives the person you select (called the “attorney-in-fact”) the power to transfer your assets to your standby trust.

If you die suddenly, however, there obviously will not be time to transfer your assets to the trust and your property must go through probate. State laws regarding the use and acceptance of a power of attorney may vary.

Please click below to watch a two-hour webinar entitled How to Protect Your Assets from the Expenses of Probate and Long-Term Care, along with how it fits into all of our Four Levels of Planning.

https://youtu.be/RQeZ-Bw7QpM

For Additional Information:

What is Probate?

Why Most People Want to Avoid Probate

How Does a Revocable Trust Avoid Probate?

What About Irrevocable Living Trusts?

Choosing a Trustee

Avoiding Estate Taxes

Estate Planning FAQs